Mathematics is extremely important in all of our daily lives whether we know it or not. However a lot of students have trouble with mathematics, and this can happen for a variety of reasons. It may be boring, listening to new rules and formulas that have no conceivable use in reality, often directly leading to the second problem. If a student-regardless of whether they’re a pre-schooler or working on their PhD-doesn’t have a firm enough grasp on older materials, the new stuff will get increasingly more difficult over time. And this is never more prevalent than in math.

I will now begin to describe the basics of mathematics, from basic counting through to the areas of arithmetic, algebra, geometry, and calculus. This will thus be an extremely quick lesson, but I hope it will nonetheless be of value, if only for you to better understand my method for the more complex information that will come later.

Starting with the very beginning, we have the numbers. There are a variety of different systems of numbers used across space and time, however the most common are the Arabic numerals shown below:

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Every number, no matter how large or small, is composed of these basic building blocks. When you are counting things individually, “one-by-one” or more precisely unit-by-unit, you are moving incrementally along the above line, using 0 or zero if nothing is there at all. Remembering the above order is crucial, as it is used in building larger numbers:

10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23

As you saw before, the numbers 0-9 are first written individually, but in order to make larger numbers they are required to combine. First the number 1 is placed in front of each of the others, and then 2, 3, and so on, until we reach 99. At this point you repeat the previous process over again but on a higher level, starting with 100, 101, 102…through to 109, 110, 111, 112…all the way to 199, 200, 201…and then 999, 1000, 1001…in a pattern that continues indefinitely.

Numbers are used throughout the world, and not just for simple unit-by-unit counting as seen above. This is where the study of quantity, or arithmetic is used. Arithmetic involves the operations used in combining or separating groups of numbers. The most basic operation is addition, from which all over forms can be derived. Two numbers are added together as follows:

2 + 3 = 5

The + indicates addition between two numbers. Looking at the list of numbers above, you can see the number 2. Move three units away from zero past 2 and you’ll get 5. The = is the equals sign, and it indicates that everything on the right(in this case the addition of 2 and 3) and on the left(in this case the number 5) have the same value. Now let’s look at the other basic operations at work:

7 – 5 = 2

2 × 4 = 8

9 ÷ 3 = 3

The first is subtraction, which is addition in reverse. In the example used, you find 7 on the line and move five units towards zero in order to get 2. The next is multiplication, which is a basically a series of additions. In the example we are looking for the result of adding four 2‘s (or two 4‘s) together, which is 8. And finally, division is the opposite of multiplication, instead asking how many 3‘s added together will result in the number 9(which unlike multiplication cannot be done the other way around). It is best to remember like this rather than to memorize large multiplication tables, because it allows you to better see how the numbers all fit together, in addition to saving time. There are several easily recognizable patterns that can arise through this method(ie. 2 × 10 = 20, 3 × 10 = 30) and it allows you to better understand how zero works(try figuring out why 5 × 0 = 0 or 0 ÷ 6 = 0 using my above explanations).

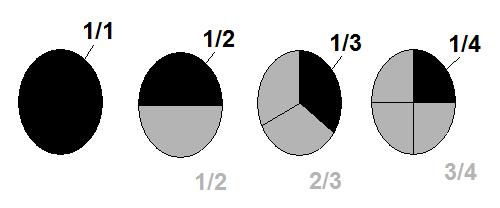

A further use for division is fractions. The example 9 ÷ 3 = 3 can also be written as 9/3 = 3, with 9/3 being the fraction. Aside from division, fractions can represent the different parts of a larger number, such as one half(1/2) or three-quarters(3/4). Some fractions are illustrated below as segments of circles, each of which represents a whole number, in this case 1.

No matter now much we break up the circles, their parts will always add up to one. One half(1/2), or one part of two, added to another half makes two halves(2/2), or two parts of two. But rather than keep it in this form, we would use division again in order to simplify: 2 ÷ 2 = 1. Likewise:

1/3 + 1/3 + 1/3 = 3/3 = 3 ÷ 3 = 1

1/4 + 1/4 + 1/4 + 1/4 = 4/4 = 4 ÷ 4 = 1

Fractions are proper if the numerator on top is less than the denominator on the bottom, indicating a value between zero and one. They are improper if it is possible to further reduce them, as is the case with 2/4, which can be reduced to 1/2(and from the images above we see that they are indeed of equal size) by dividing both the numerator and denominator by the same number, in this case 2. 9/3 is also improper, being further reduced to 3/1 or simply 3. In the case of 8/3, keep in mind that this is still division as explained earlier, so that within eight units, only two 3‘s can add together, leaving 2 as a remainder. Thus, 8/3 is reduced to 2 & 2/3.

In addition to fractions, numbers can also be written in decimal format, which will include the whole number(even if it is zero), followed by a decimal(.) and the fractional amount. A good way to start seeing how this works is to compare the multiples of 1/10 compared to their decimal(wherein “deci-” means 10) forms, and to deduce the rest from there. In some examples I’ve put fractions into improper forms in order to make 10 the denominator.

1/10 = 0.1, 2/10 = 0.2, 3/10 = 0.3, etc.

1/5 = 2/10 = 0.2, 1/2 = 5/10 = 0.5, 4/5 = 8/10 = 0.8

7/5 = 1 & 2/5 = 1 & 4/10 = 1.4

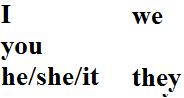

All the equations used up until now contain numbers that were already known to us, but as we go further we have to explore algebra, which introduces letters as placeholders for unknown numbers, commonly referred to as variables. For instance, to use the earlier adding example, 2 + x = 5 has now been turned into an algebraic equation. We of course know that x = 3, but let’s stay with the problem to see how we can better isolate x.

To do this, you have to do the same operation on both sides of the ‘equals’ sign, because in order to remain equal, anything done to one must be done to the other(as seen before with altering fractions). So, what series of operations can you perform to make 2 + x into x? Let’s try subtracting 2:

2 + x – 2 = 5 – 2

x = 3

But we already knew that, right? The same thing can be done using any of the other operations, so try it out! These types of equations are quite easy to perform if there is only one unknown number, but things start to get trickier once more variables are introduced:

a + b + c, 2 × (a + b)

(b × h) ÷ 2, a × b

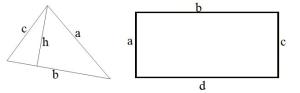

The above expressions each have more than one variable, making them impossible to solve on their own. Thankfully these are equations that are related to shapes in space, meaning that we will be able to obtain some or all of the variables by measurement. This is the next subdivision of mathematics, known as geometry. The top two expressions can be used to determine the perimeter, or complete path around, of a triangle or rectangle respectively. The bottom two are used to calculate the area within each of these shapes. a, b, and c are the sides of the shapes, while h refers to the height of a triangle from b to the opposite corner while forming a right angle(which will be explained soon).

These each have a constant number of sides, which define the name of the shape. A triangle has three and a quadrilateral four, a pentagon five and so on. They can be defined even further by their angles. An angle is the corner between two lines, in this case the sides of the given shape. A quadrilateral for instance has four angles, the sizes of which determine the type. The 90° angle is called a right angle, and a quadrilateral possessing four of these is called a rectangle(furthermore, if it has four right angles in addition to four equal sides(ie. a = b = c = d), then it is called a square). Other types of angles include acute(less than 90°), obtuse(between 90° and 180°), straight(180°), and reflex(greater than 180°).

These each have a constant number of sides, which define the name of the shape. A triangle has three and a quadrilateral four, a pentagon five and so on. They can be defined even further by their angles. An angle is the corner between two lines, in this case the sides of the given shape. A quadrilateral for instance has four angles, the sizes of which determine the type. The 90° angle is called a right angle, and a quadrilateral possessing four of these is called a rectangle(furthermore, if it has four right angles in addition to four equal sides(ie. a = b = c = d), then it is called a square). Other types of angles include acute(less than 90°), obtuse(between 90° and 180°), straight(180°), and reflex(greater than 180°).

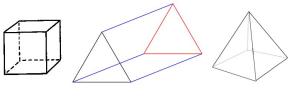

The shapes shown so far are two-dimensional, but there also exist three-dimensional objects, along with a new method of measuring them known as volume. Here are a few examples:

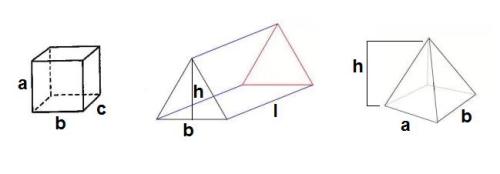

The two on the left are both prisms, one rectangular and the other triangular. Their volumes can be calculated simply enough, by taking the area of one of the two equal faces and multiplying by the distance between them. The third object is a pyramid, whose volume is equal to the area of the base multiplied by height, and then divided by 3. For example:

The two on the left are both prisms, one rectangular and the other triangular. Their volumes can be calculated simply enough, by taking the area of one of the two equal faces and multiplying by the distance between them. The third object is a pyramid, whose volume is equal to the area of the base multiplied by height, and then divided by 3. For example:

Using the variables given, the volume of each object can be shown by the equations a × b × c, (b × h × l) ÷ 2, and (a × b × h) ÷ 3, respectively. Notice that for the prisms we’re just using the equations for area from earlier while including an extra dimension, such as l in the triangular prism’s case. For the pyramid we start to calculate the volume just like we would the prisms, but we then have to then divide by 3. This is because a pyramid has exactly 1/3 the volume of a rectangular prism with the same base and height.

But let’s go back to the rectangular prism for a moment. Unlike the triangular variant, it is less obvious which two faces were the bases for the equation, right? This is because you could take any two opposite faces and consider them the bases. In the equation a × b × c, any of the three variables could be the length, with the other two representing the area of the base.

Going one step further, if a = b = c, then we have a cube, a special case where all six sides of the object are equal(or in other words, squares). Thus the area of each side could be written as a × a while the volume of the cube could be a × a × a. However in practice we instead take the number of equal variables and place them in a superscript known as an exponent. To illustrate:

a × a = a²

a × a × a = a³

Now let’s try to replace these variables with numbers again for a moment. If a = 3, then a² = 3² = 3 × 3 = 9. This means that a square with 3 units on each side will have 9 units overall. Furthermore, a cube where a = 3 will consist of 3³ = 3 × 3 × 3 = 27 units. But aside from squares and cubes, you can also have a4, a5, etc., and even a1/2, which is more commonly seen as √a and known as a square root. Just like division is the reverse of multiplication, the square root is the reverse of the square. For example, if 32 = 9 then √9 = 3. Similarly, you can also have a cube root and even a quarter root, but we’ll stick with the square ones for now.

These new methods of counting start to get very convenient as we expand our scope one step further, and include another dimension, time, as we explore the last main division of mathematics: calculus, the study of change.

To understand calculus you must first understand functions. Consider a variable x which, for any possible value it could have, there exists a unique variable y to correspond to it. That is, y is a function of x, or y = f(x). For example, if x was velocity and y was distance traveled, there would be an obvious connection between the two, and no two velocities would yield the same distance traveled. These results could then be plotted onto a graph, complete with two number lines called the x-axis and y-axis, both representing every possible value these variables can have. The spot where the two axes meet is known as the origin, which is where both x and y are equal to zero. Here are some examples:

These three graphs represent linear functions, which are aptly named because they are all straight lines. The first graph is pretty straightforward, no pun intended; for every value of x, y = 7. Thus, it is a line that makes a right angle with the y-axis. The others however have y increasing in value the greater that x becomes. All three lines can be written in the form y = mx +b, where b is the y-intercept(ie. the point where x = 0) and m is the slope, or rate of change of the line. When the slope is not so obvious, it can be calculated by taking the change in value of y(written as Δy) divided by the change in value of x(written as Δx) between two points along the line. For example, in the y = 2x + 3 graph between the origin and x = 1, y would have changed from 3 to 5, while x would change from 0 to 1. Thus:

m = Δy ÷ Δx

m = (5 – 3) ÷ (1 – 0) = 2 ÷ 1 = 2

The next logical step forward would be to move on to nonlinear functions, but that will first require going back through the variety of mathematical topics touched upon here and further expanding on them. And that is the goal for next time, when I hope to see you return.